Following our City Academy Short Writing Competition 2022, We are delighted to introduce Heike Ellwood, the winner, with her entry What Yuri Got.

What Yuri Got

Christa’s birthday breakfast was at six-thirty on a Friday in October. It was the autumn school holidays, but her grandparents were early risers and up at five every morning to pin back the curtains, fire up the tiled stove and prepare the washstand. Grandfather was a foreman at the foundry. Grandmother worked at home, as a patternmaker for a local seamstress.

There was cocoa for Christa, and soft milk rolls with butter and strawberry jam. She was allowed to blow out the thirteen candles on her cake, but the cake was to remain intact until the afternoon. Mother was expected at five to spend the weekend. By then, the two cosmonauts would have received their medals, which was to happen at the exact same time but in different cities. While the first man in space was in Erfurt, the woman whom the papers called Valya was here, in Karl-Marx-Stadt. Christa hadn’t been selected for the Young Pioneers’ Welcome Committee and had begged to go to the parade instead, but her grandfather hated everything to do with the Russians and wouldn’t hear of it. He eventually permitted her to watch the whole thing downstairs at Fräulein Doller’s. She owned a television set and had invited everybody in the building. ‘Under the condition that you will never mention any of it to me,’ he said. ‘I do not care to know. These people and their dreck.’ He would have said more, but grandmother shushed him because it wasn’t good dwelling on these things, and also, one had to be careful. Christa understood. Grandfather had only been released in forty-eight from a camp in Kazakhstan, in a state so feeble his two younger brothers hauled him home from the station in a handcart. Each Saturday afternoon, he met with other veterans at the Volkshaus bar, then carried on drinking in the attic room, taking swigs of potato spirit from his battered army canteen until darkness engulfed him or he got hungry. But not this weekend. This weekend, mother would come. The Volkshaus get-together had been cancelled and they would all sit down to Peach Melba and a game of rummy.

Christa’s gifts were a new fountain pen, two books and a purple scarf her grandmother had knitted. She draped it over Christa’s shoulders in front of the hallway mirror and turned her around, holding her at arm’s length like a prize. ‘Look at you, little mouse. It really compliments your hair.’ Christa’s hair was nondescript in colour, bobbed and practical, and the scarf didn’t change that. Her grandfather, putting on his shoes, said, ‘A ravishing beauty you will grow up to be. Like your grandmama!’ They all laughed because her grandmother was no beauty. She was short and stout and solid like a tree trunk, and Christa took after her. Not so Christa’s mother, who was dark and willowy, dropped down our chimney by the wrong stork, as Christa’s grandfather joked. Since her divorce, she lived in Saxony-Anhalt with a married man eighteen years her senior. It hadn’t been practical for Christa to live with them, on account of her mother’s heart murmur and the new lover’s testiness around children.

Just after ten, Gabriele turned up outside, shouting Christa’s name. Christa was on the sofa with the new books and her feet up, which was only acceptable when grandfather wasn’t home.

‘That girl,’ her grandmother said with a sigh. She was bent over her table by the window, pinning paper shapes onto a stretch of calico. ‘Tell her she needs to pipe down and learn how to work a doorbell.’ She got up and peered outside from under her glasses because Gabriele was now imitating an echo. Christa! -ista! -ista! She had little decorum and a voice trained by making herself heard over four younger brothers, a waking-the-dead voice, as Christa’s grandfather put it. ‘That silly girl is lucky people have no eggs to spare,’ her grandmother said, waving at Gabriele to shut up. Then she turned to Christa. There was a dark stain in the corner of her mouth where she parked her graphite pens. ‘Off you go. Lunch at one.’

Gabriele was waiting in the back yard. She was a tall, happy-go-lucky girl of fifteen. She already teased her hair and had been seen wearing lipstick just a few months ago, although Christa didn’t really believe this. Her performance at school was less than stellar and her spelling was particularly weak, but when around adults, she had good manners, irreproachable manners in fact. Sometimes, Christa helped her with the homework in exchange for boiled sweets or stringy Cuban oranges. Gabriele’s mother worked at the greengrocers.

‘Happy birthday, comrade, you’re catching up!’ The girls hugged. Gabriele handed Christa a cream-coloured envelope. It contained a simple postcard onto which she had pasted a picture of Yuri Gagarin in his space helmet, lying back calmly in his seat on board Vostok 1 with a serene little smile on his face, as if he already knew that luck would be with him and that everything would turn out just fine. She had drawn a bunch of flowers at the margin with a blue felt pen. They went and perched on the wash house steps.

‘Are you going to the parade?’ Gabriele asked.

‘I’m not allowed.’ The lawn was covered in yellow leaves. A line of laundry hung limply under the autumn sun. ‘I’ll watch it on the television. We have been invited.’

‘Lucky you, you’ll get to see them both then. My parents insist I go. I hate crowds. All that stupid waving. And I won’t get to see Gagarin. Just five seconds or so of Tereshkova. She looks like a dish of cabbage soup.’ She sighed. ‘He is so handsome.’

‘Ugh,’ Christa said. ‘He’s too short for you to kiss.’

‘I’ll put him on a step.’

‘He has funny teeth.’

‘He can keep his mouth shut.’

‘You couldn’t even talk to him. Your Russian is so bad.’

Gabriele grinned. ‘Well, if tovarich Gagarin wants me, he had better learn German.’ She pouted and kissed the air. Beyond the hedge, a tram rumbled past, bells ringing. Two women were shouting a conversation about a man named Herbert who was in the municipal hospital. Gabriele threw back her head and cried Oh God, Herbert just died! and they bent double with stifled laughter. Then they went to the park and to the bakery were Gabriele bought them a chocolate-covered palmier to share.

‘Tell me what Gagarin’s like,’ Gabriele said when they parted.

‘I won’t see him in real life, you know.’

‘Tell me anyway.’

The day was already tinged with a hint of dusk when Christa went downstairs. Fräulein Doller was in her sixties. Her hug was generous, vaguely desperate even. She had her dresses altered by Christa’s grandmother because her bosom was enormous. In her cleavage, there was a linen handkerchief doused in Eau de Cologne. Her apartment was decorated with cherry-blossom wallpaper. Christa counted seven elderly neighbours, two of whom were talking very loudly because they were hard of hearing, and Frau Hilbert with her son Gerhard who had been in a swimming accident when he was Christa’s age, which meant he couldn’t speak or fix his eyes on any object for longer than a few moments.

The television set was in a rosewood cabinet, switched on but silent. On top of the set was a little porcelain penguin whose head was nodding frantically with each vibration in the floorboards. Christa peeked at the screen. She could see the Strasse der Nationen, thronged with people. The streetlights were switched on although it wasn’t dark yet. The camera cut from person to person and then over the crowds from a vantage point so high that almost the full length of the street was visible. The programme switched back to the inside of the city hall. An enormous banner with the profiles of Marx, Engels and Lenin had been draped above the entrance. Underneath, men in suits and uniforms clustered, shuffling their feet. Some smoked cigarettes.

Around the sitting-room there were crystal bowls with peanut puffs, salted sticks and chocolate flakes. Fräulein Doller ladled fruit punch into glasses. Christa was asked to give a report about school and had to reassure everybody that her grandparents were very well. She was allocated a seat on the sofa next to Gerhard. His mother was on his other side, feeding him biscuits smothered in butter from a paper napkin while talking to Christa. Gerhard’s hands lay on his lap, twisted inwards like crosiers. They would take the train to the Baltic Sea for Christmas to visit her sister, his mother explained. She was looking forward to the trip but also dreaded it a little. Gerhard was very good with trains, so much so that it was hard to get him off, very hard indeed, because all he knew was the present moment, which meant he could never understand that there would always be another train to ride. In the background, on the television, a cavalcade of cars slowly made its way down the street, and then it was back to Marx and Lenin and the cigarette smoke. Gerhard’s mother said that it was necessary to tire him out before going on a trip. It made him easier to handle.

‘They’ve arrived!’ Herr Heidrich jumped up and turned a dial. Music filled the room. A Young Pioneer brass band walked into the auditorium playing a march. The commentator sounded breathless, nearly tipping into screams. The victories of socialism! The excellence inherent in the international working classes! The heroic achievements of this humble, young worker! The band walked off to the right and Valentina Tereshkova appeared, waving, and smiling.

‘She is wearing a house dress,’ Gerhard’s mother said. ‘Why is she wearing a house dress?’

‘She is a pretty lady,’ one of the old men said. ‘Fresh as an apple. She doesn’t need paint on her face.’ Tereshkova was making her way through the audience, then took her seat in the front row, still waving and clapping her hands to the music.

The programme switched to Erfurt. Christa bent forward. Gabriele would quiz her about every detail.

The music didn’t change, miraculously, as if the same band was playing its cheerful tune across the country, in every city hall. There came Gagarin. He was wearing a uniform and held a bunch of carnations. He walked, beaming, through the crowd. Hands were waving around him like startled birds under the resplendent chandeliers. His face was made for smiling, Christa thought. His teeth were fine after all. His eyes were bright and gave him an expression of sharpness. Was there a hint of surprise on his face at all the fuss that was made over him? Christa couldn’t decide whether he was good-looking.

There was movement on his left. A young woman in a smart suit broke through a row of soldiers and flung herself at him. She hugged him tight and kissed him, left and right, twice. She kept holding him for a moment, cradling his neck in her hand and said something in his ear. His grin widened. She was beautiful, with dark wavy hair. The men in his entourage looked on with glee.

The sitting-room had fallen silent. Gagarin and his men walked on to the front row. Fräulein Doller turned to Christa.

‘Wasn’t that your mother?’ she said. ‘It was her, wasn’t it?’

‘Can you believe it!’ one of the deaf women shouted. ‘That was Inge! What does she think she’s doing!’

‘It was Inge, as I live and breathe,’ Gerhard’s mother said. She kept pointing at the television set as if she had forgotten how to lower her hand.

‘The police will arrest her,’ an old man said.

‘Don’t be stupid. Why would they?’ another one said. ‘Maybe out of envy. He liked it.’ He turned to Christa. ‘Your mother is a beauty. She can kiss me anytime she likes. Heavens, I might travel to space myself if this is what I get when I come back!’ His wife elbowed him, but the other men burst out laughing.

Christa had turned bright red. The whole room was now discussing whether Inge would be in the papers tomorrow, and what the consequences might be. Christa stared at her knees. One of Gerhard’s hands lifted, motioning for another biscuit, but his mother didn’t see it.

‘I have to be back upstairs,’ Christa said to no-one in particular. ‘It’s my birthday.’

‘Oh, little heart’ Fräulein Doller said, ‘we didn’t know.’ And somebody else said, ‘You should have told.’

Mother had sent a telegram (‘Otto suddenly sick, cannot make it. Loving birthday greetings.’). Christa’s grandparents never spoke ill of her in front of Christa, but when her grandfather came home from his shift, grandmother pulled him into the kitchen and closed the door behind them. Their voices were urgent but muffled, and the only words Christa could make out were ‘-deserve this’, but it remained unclear who deserved what, or not.

Her grandfather suggested they invite Gerhard and his mother, there would be a lot of cake left otherwise. Gerhard liked cake and why not make a party of it, but Christa said, no, no, the cake was too good to be shared.

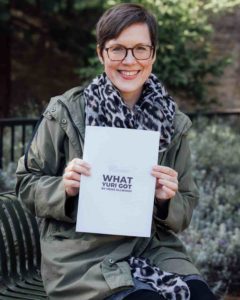

About Heike Ellwood

While my day job is spent in IT, I love writing short stories and silly poetry. I particularly enjoy writing in English, a language with great capacity for nuance and humour (and far fewer pointless compound nouns than my native German). In addition to writing, I love hiking, politics, local history, exploring tea shops with my husband and curling up with our two cats.